威克菲尔德的牧师 02 破产与迁移

The temporal concerns of our family were chiefly committed to my wife’s management, as to the spiritual I took them entirely under my own direction. The profits of my living, which amounted to but thirty-five pounds a year, I made over to the orphans and widows of the clergy of our diocese; for having a sufficient fortune of my own, I was careless of temporalities, and felt a secret pleasure in doing my duty without reward. I also set a resolution of keeping no curate, and of being acquainted with every man in the parish, exhorting the married men to temperance and the bachelors to matrimony; so that in a few years it was a common saying, that there were three strange wants at Wakefield, a parson wanting pride, young men wanting wives, and alehouses wanting customers. Matrimony was always one of my favourite topics, and I wrote several sermons to prove its happiness: but there was a peculiar tenet which I made a point of supporting; for I maintained with Whiston, that it was unlawful for a priest of the church of England, after the death of his first wife, to take a second, or to express it in one word, I valued myself upon being a strict monogamist. I was early initiated into this important dispute, on which so many laborious volumes have been written. I published some tracts upon the subject myself, which, as they never sold, I have the consolation of thinking are read only by the happy few. Some of my friends called this my weak side; but alas! they had not like me made it the subject of long contemplation. The more I reflected upon it, the more important it appeared. I even went a step beyond Whiston in displaying my principles: as he had engraven upon his wife’s tomb that she was the only wife of William Whiston; so I wrote a similar epitaph for my wife, though still living, in which I extolled her prudence, economy, and obedience till death; and having got it copied fair, with an elegant frame, it was placed over the chimneypiece, where it answered several very useful purposes. It admonished my wife of her duty to me, and my fidelity to her; it inspired her with a passion for fame, and constantly put her in mind of her end.

我家庭的物质问题主要由我妻子负责,至于精神问题,我完全自己负责。我的生活收入,总共只有每年三十五英镑,我将其转让给我们教区的孤儿和寡妇;因为我有自己的足够的财富,所以我对物质并不在意,并且在做我的职责而不需要任何回报时感到内心的愉悦。我还决定不雇用任何助理,并认识我们村庄里每个人,劝说已婚男士遵循节制,向未婚男士劝说结婚;这样在几年后,人们在wakefield就会说,缺乏教士的骄傲,年轻人缺乏妻子,酒吧缺乏顾客。结婚一直是我最喜欢的话题,我写了几个宣传它快乐的诗篇;但是,我一直坚持支持一种特殊的主张,即我认为教会的牧师,在第一位妻子去世后,无法再婚,或者用一句话来说,我自豪地认为自己是一个严格的单婚主义者。我早就参与到了这个重要的争议中,这个争议已经引发了许多辛苦的卷宗。我本人也写了一些关于这个主题的小册子,但由于从未出售,我很欣慰地认为只有那些幸福的少数人在阅读它们。有些朋友称这是我的弱点,但唉!他们没有像我一样把它作为长期的考虑对象。随着我对它的反思,它似乎变得越来越重要。我甚至比Whiston更加展示我的原则:就像他在妻子的墓碑上雕刻了她是William Whiston的唯一妻子一样,我也为我的妻子写了一张类似的墓碑,虽然她还活着,在上面我赞美她的谨慎、节俭和顺从,直到死亡;然后我把它打印得很漂亮,并放在壁炉旁,这样它可以发挥几个非常有用的作用。它提醒我的妻子她应该对我的责任,提醒我向她的忠贞,激发她对名声的热情,并始终让她想起她的末日。

It was thus, perhaps, from hearing marriage so often recommended, that my eldest son, just upon leaving college, fixed his affections upon the daughter of a neighbouring clergyman, who was a dignitary in the church, and in circumstances to give her a large fortune: but fortune was her smallest accomplishment. Miss Arabella Wilmot was allowed by all, except my two daughters, to be completely pretty. Her youth, health, and innocence, were still heightened by a complexion so transparent, and such an happy sensibility of look, as even age could not gaze on with indifference. As Mr. Wilmot knew that I could make a very handsome settlement on my son, he was not averse to the match; so both families lived together in all that harmony which generally precedes an expected alliance. Being convinced by experience that the days of courtship are the most happy of our lives, I was willing enough to lengthen the period; and the various amusements which the young couple every day shared in each other’s company, seemed to increase their passion. We were generally awaked in the morning by music, and on fine days rode a-hunting. The hours between breakfast and dinner the ladies devoted to dress and study: they usually read a page, and then gazed at themselves in the glass, which even philosophers might own often presented the page of greatest beauty. At dinner my wife took the lead; for as she always insisted upon carving everything herself, it being her mother’s way, she gave us upon these occasions the history of every dish. When we had dined, to prevent the ladies leaving us, I generally ordered the table to be removed; and sometimes, with the music master’s assistance, the girls would give us a very agreeable concert. Walking out, drinking tea, country dances, and forfeits, shortened the rest of the day, without the assistance of cards, as I hated all manner of gaming, except backgammon, at which my old friend and I sometimes took a twopenny hit. Nor can I here pass over an ominous circumstance that happened the last time we played together: I only wanted to fling a quatre, and yet I threw deuce ace five times running. Some months were elapsed in this manner, till at last it was thought convenient to fix a day for the nuptials of the young couple, who seemed earnestly to desire it. During the preparations for the wedding, I need not describe the busy importance of my wife, nor the sly looks of my daughters: in fact, my attention was fixed on another object, the completing a tract which I intended shortly to publish in defence of my favourite principle. As I looked upon this as a masterpiece both for argument and style, I could not in the pride of my heart avoid showing it to my old friend Mr. Wilmot, as I made no doubt of receiving his approbation; but not till too late I discovered that he was most violently attached to the contrary opinion, and with good reason; for he was at that time actually courting a fourth wife. This, as may be expected, produced a dispute attended with some acrimony, which threatened to interrupt our intended alliance: but on the day before that appointed for the ceremony, we agreed to discuss the subject at large. It was managed with proper spirit on both sides: he asserted that I was heterodox, I retorted the charge: he replied, and I rejoined. In the meantime, while the controversy was hottest, I was called out by one of my relations, who, with a face of concern, advised me to give up the dispute, at least till my son’s wedding was over. “How,” cried I, “relinquish the cause of truth, and let him be an husband, already driven to the very verge of absurdity. You might as well advise me to give up my fortune as my argument.” “Your fortune,” returned my friend, “I am now sorry to inform you, is almost nothing. The merchant in town, in whose hands your money was lodged, has gone off, to avoid a statute of bankruptcy, and is thought not to have left a shilling in the pound. I was unwilling to shock you or the family with the account till after the wedding: but now it may serve to moderate your warmth in the argument; for, I suppose, your own prudence will enforce the necessity of dissembling at least till your son has the young lady’s fortune secure.”—“Well,” returned I, “if what you tell me be true, and if I am to be a beggar, it shall never make me a rascal, or induce me to disavow my principles. I’ll go this moment and inform the company of my circumstances; and as for the argument, I even here retract my former concessions in the old gentleman’s favour, nor will I allow him now to be an husband in any sense of the expression.”

在这种情况下,也许是因为频繁地推荐结婚,我的长子刚刚离开大学时,他就对邻居牧师的女儿产生了情感,她是教会的一位尊敬的人,也处于有利的经济状况下;但是,她的美好并不在于财富。艾拉贝拉·威尔默被所有人称赞,除了我的两个女儿,她的青春、健康和无邪,一个如此透明的肤色和如此快乐的感性相结合,即使年老的人也无法面对不以为然。因为我知道我可以为我的儿子提供一个非常优秀的婚姻安排,威尔默先生对这一事宜并不反感。因此,两家人生活在预期的和谐之中,这通常是预期的联盟之前的情况。我被实践所说服,提婚期最快可以延长一段时间,而两个年轻人每天在一起度过的各种娱乐似乎增加了他们的感情。我们每天早上都会被音乐唤醒,而在晴朗的日子里,我们会去狩猎。午餐之前和午餐之后,女士们会花时间打扮和学习:她们通常会读一页,然后在镜子前仔细地审视自己,即使是哲学家也会承认这种情况下镜子上的页面通常是最美丽的页面。我的妻子在午餐时会主导:因为她坚持自己切割每一样菜肴,这是她母亲的做法,所以在这些场合,她会向我们讲述每一道菜的历史。我们午餐后,为了防止女士们离开我们,我通常会指示清除桌子;有时,与音乐师的协助,女孩们会给我们带来非常令人愉悦的音乐会。散步、喝茶、乡村跳舞和罚金都可以使剩下的时间更快地消逝,而我厌恶所有形式的游戏,除了我和我的老朋友在一起时的游戏棋,这是我们最终会下注两便的游戏。在我和我的老朋友最后一次一起玩这个游戏时,有一个令人不安的情况发生:我只想抛出一个四,但是我连续抛出了五次两 ace 和五。这样的日子一直持续到我们最终决定确定年轻夫妇结婚的日子,他们似乎非常渴望结婚。在婚礼准备中,我不必描述我妻子的繁忙重要性,或者我的女儿的窥探眼光;实际上,我的注意力被另一个目标吸引,那就是我打算很快发表我自己的一篇小册子,以支持我最喜欢的原则。我认为这是一篇大师级的文章,至少在论点和写作风格上是如此,我在心中为自己骄傲地想到,我不会有任何疑问地获得他的认可;但是,直到太迟了,我才发现他非常坚定地支持相反的观点,而且有充分的理由;因为他当时已经追求第四任妻子。这当然导致了一场尖锐的争议,带有一些恶意,挑战我们的预期联盟;但是,在结婚当天的前一天,我们同意详细讨论这个问题。两方都表现得很有气度地进行了辩论:他声称我是异端的,我则反驳他的指责;他回答,我反驳。在此期间,辩论最激烈的时候,我被一个我的亲戚召见,他脸色阴沉地告诉我,要我放弃这个争议,至少在我的儿子结婚之前;“你怎么能放弃为真理而斗争的原因,让他成为一个已经靠近愚蠢的丈夫?”他说,“你可以向我透露这个消息,就像你不会在你的儿子获得年轻女士的财产之前惊吓你或你的家人一样。”“你的财产,”我的朋友回答,“我现在很抱歉地告诉你,已经几乎不存在了。你在镇上的商人,在他的手中存放你的钱,为了避免倒闭的法律,已经跑了,据说他没有留下一个便士;我不想伤害你或你的家人,所以我一直在推迟告诉你这个账单,但现在它可能会减少你在争议中的激情,因为你的自己的明智会强制你在你的儿子获得年轻女士的财产之前装扮下来。”“好的,”我回答,“如果你所说的是真的,如果我真的要成为一个乞丐,那么即使我成为一个乞丐,我也不会成为一个坏人,也不会放弃我的原则。我现在就要去告诉大家我的情况;至于争议,我现在就会否认我以前对老人的任何妥协,也不会同意他在任何意义上成为一个丈夫。”

It would be endless to describe the different sensations of both families when I divulged the news of our misfortune; but what others felt was slight to what the lovers appeared to endure. Mr. Wilmot, who seemed before sufficiently inclined to break off the match, was by this blow soon determined: one virtue he had in perfection, which was prudence, too often the only one that is left us at seventy-two.

为我们的不幸所做的消息让我们的两家人感到非常沮丧,但恋人们的感受比他们的感受要轻微得多。威尔默先生似乎在事件发生之前已经足够倾向于解除这一婚约,但是这一打击让他迅速决定:在七十二岁时,他拥有的唯一一项完美的美德就是谨慎,这是我们常常在年老时才剩下的唯一一项美德。

A migration—The fortunate circumstances of our lives are generally found at last to be of our own procuring.

迁移——我们生命中幸运的情况最终被发现是我们自己采取措施引发的。

The only hope of our family now was, that the report of our misfortunes might be malicious or premature: but a letter from my agent in town soon came with a confirmation of every particular. The loss of fortune to myself alone would have been trifling; the only uneasiness I felt was for my family, who were to be humble without an education to render them callous to contempt.

Near a fortnight had passed before I attempted to restrain their affliction; for premature consolation is but the remembrancer of sorrow. During this interval, my thoughts were employed on some future means of supporting them; and at last a small Cure of fifteen pounds a year was offered me in a distant neighbourhood, where I could still enjoy my principles without molestation. With this proposal I joyfully closed, having determined to increase my salary by managing a little farm.

我们家族唯一的希望是,对我们的不幸的报告可能是恶意的或过早的;但是,来自城里我的代理人的信件很快证实了每一个细节。财产的丧失对我个人来说是微不足道的;我唯一的不安是我的家人,他们将不再尊贵,而不会有受到蔑视的教育来使他们麻木。

已经过去了接近两个星期,我才尝试克制他们的悲伤;因为过早的安慰只是记忆的痛苦。在这段时间里,我的思想被以后支持他们的一些方法所吸引。最终,我得到了一份价值每年15英镑的小教区工作,这是在一个遥远的地方,我可以在那里没有受到干扰地享受我的原则。我高兴地接受了这个建议,已经决定通过管理一个小农场来增加我的薪水。

Having taken this resolution, my next care was to get together the wrecks of my fortune; and all debts collected and paid, out of fourteen thousand pounds we had but four hundred remaining. My chief attention therefore was now to bring down the pride of my family to their circumstances; for I well knew that aspiring beggary is wretchedness itself. “You cannot be ignorant, my children,” cried I, “that no prudence of ours could have prevented our late misfortune; but prudence may do much in disappointing its effects. We are now poor, my fondlings, and wisdom bids us conform to our humble situation. Let us then, without repining, give up those splendours with which numbers are wretched, and seek in humbler circumstances that peace with which all may be happy. The poor live pleasantly without our help, why then should not we learn to live without theirs. No, my children, let us from this moment give up all pretensions to gentility; we have still enough left for happiness if we are wise, and let us draw upon content for the deficiencies of fortune.” As my eldest son was bred a scholar, I determined to send him to town, where his abilities might contribute to our support and his own. The separation of friends and families is, perhaps, one of the most distressful circumstances attendant on penury. The day soon arrived on which we were to disperse for the first time. My son, after taking leave of his mother and the rest, who mingled their tears with their kisses, came to ask a blessing from me. This I gave him from my heart, and which, added to five guineas, was all the patrimony I had now to bestow. “You are going, my boy,” cried I, “to London on foot, in the manner Hooker, your great ancestor, travelled there before you. Take from me the same horse that was given him by the good bishop Jewel, this staff, and take this book too, it will be your comfort on the way: these two lines in it are worth a million—I have been young, and now am old; yet never saw I the righteous man forsaken, or his seed begging their bread. Let this be your consolation as you travel on. Go, my boy, whatever be thy fortune let me see thee once a year; still keep a good heart, and farewell.” As he was possessed of integrity and honour, I was under no apprehensions from throwing him naked into the amphitheatre of life; for I knew he would act a good part whether vanquished or victorious.

我做出决定后,下一个关注点是收集我的财产残渣;我收集了所有的债务,付清了所有的债务,我们剩下的是只有400英镑。因此,我的主要任务现在是降低我的家人的骄傲,让他们适应他们的情况;因为冒充贫穷是悲惨的。「你们当然不会是无知的,我的孩子们,」我喊道,「我们的不幸是无法预防的;但是,谨慎可以做很多事情,使它的影响受到限制。我们现在是穷人了,我的爱人们,智慧告诉我们应该适应我们贫困的情况。那么,没有理由怨恨的情况下,我们就应该放弃那些让数百万人苦恼的奢侈,寻求在更谦卑的环境中获得和平,所有人都可以快乐。穷人可以高兴地生活而不需要我们的帮助,那么为什么我们不应该学会在不需要他们的帮助下生活?不,我的孩子们,从现在开始,我们应该放弃对高雅的一切幌子;如果我们聪明,我们还有足够的东西让我们快乐,让我们将内容用于弥补财富的不足。」由于我的长子是学者,我决定让他去市里,他的才能可以为我们的生计做出贡献,并为他自己做出贡献。朋友和家人分离是贫穷伴随的最为悲痛的情况之一。分离的那一天很快到来了,我们第一次分散。我的儿子离开他的妈妈和其他人,他们混合着眼泪和吻。他来请求我的祝福。我从心底为他祝福,加上五个英镑,这是我现在唯一可以传递的财富。「你要去,我的孩子,」我说,「像你的远大祖先,Hooker先生在他之前那样跑到伦敦。从我这里带走这匹马,这根杖,还有这本书,它会在你旅途中给你带来安慰:这两行文字对我来说价值一百万——我年轻时,现在老了;但是我从未见过正直的人被遗弃,或他的后裔乞讨饭碗。这可以成为你旅途中的安慰。去吧,孩子,不管你的运气如何,让我在一年的时间里看到你一次;保持一个好心态,再见。」由于他有正直和荣誉感,我不用担心将他抛弃在生命的角斗场中,因为我知道他在失败或获胜的情况下都会发挥好的表演。

His departure only prepared the way for our own, which arrived a few days afterwards. The leaving a neighbourhood in which we had enjoyed so many hours of tranquility, was not without a tear, which scarce fortitude itself could suppress. Besides, a journey of seventy miles to a family that had hitherto never been above ten from home, filled us with apprehension, and the cries of the poor, who followed us for some miles, contributed to increase it. The first day’s journey brought us in safety within thirty miles of our future retreat, and we put up for the night at an obscure inn in a village by the way. When we were shown a room, I desired the landlord, in my usual way, to let us have his company, with which he complied, as what he drank would increase the bill next morning. He knew, however, the whole neighbourhood to which I was removing, particularly Squire Thornhill, who was to be my landlord, and who lived within a few miles of the place. This gentleman he described as one who desired to know little more of the world than its pleasures, being particularly remarkable for his attachment to the fair sex. He observed that no virtue was able to resist his arts and assiduity, and that scarce a farmer’s daughter within ten miles round but what had found him successful and faithless. Though this account gave me some pain, it had a very different effect upon my daughters, whose features seemed to brighten with the expectation of an approaching triumph, nor was my wife less pleased and confident of their allurements and virtue. While our thoughts were thus employed, the hostess entered the room to inform her husband, that the strange gentleman, who had been two days in the house, wanted money, and could not satisfy them for his reckoning. “Want money!” replied the host, “that must be impossible; for it was no later than yesterday he paid three guineas to our beadle to spare an old broken soldier that was to be whipped through the town for dog-stealing.” The hostess, however, still persisting in her first assertion, he was preparing to leave the room, swearing that he would be satisfied one way or another, when I begged the landlord would introduce me to a stranger of so much charity as he described. With this he complied, showing in a gentleman who seemed to be about thirty, dressed in clothes that once were laced. His person was well formed, and his face marked with the lines of thinking. He had something short and dry in his address, and seemed not to understand ceremony, or to despise it. Upon the landlord’s leaving the room, I could not avoid expressing my concern to the stranger at seeing a gentleman in such circumstances, and offered him my purse to satisfy the present demand. “I take it with all my heart, Sir,” replied he, “and am glad that a late oversight in giving what money I had about me, has shown me that there are still some men like you. I must, however, previously entreat being informed of the name and residence of my benefactor, in order to repay him as soon as possible.” In this I satisfied him fully, not only mentioning my name and late misfortunes, but the place to which I was going to remove. “This,” cried he, “happens still more luckily than I hoped for, as I am going the same way myself, having been detained here two days by the floods, which, I hope, by tomorrow will be found passable.” I testified the pleasure I should have in his company, and my wife and daughters joining in entreaty, he was prevailed upon to stay supper. The stranger’s conversation, which was at once pleasing and instructive, induced me to wish for a continuance of it; but it was now high time to retire and take refreshment against the fatigues of the following day.

他离开只为铺平了我们自己离开的道路,这几天后我们也离开了。离开我们在那里享受过这么多宁静时光的邻里,并不是没有流泪,即使是刚刚强大的自觉也无法抑制。此外,一次七十英里的旅行,到目前为止从未超过十英里的家人,让我们感到有些不安,当我们离开时,数个贫困者还在跟随我们几英里,这使我们更加不安。第一天的旅行安全地将我们带入了 retreat 附近,我们在路边的一个小旅店过夜。当我们被安排了房间时,我像平常一样地要求旅店老板和我们在一起,他也很顺从,因为他喝的东西会增加第二天的账单。他知道我要去的地方,特别是我的房东——安格尔先生,他是我的房东,住在那里的几英里之内。这位绅士介绍他是一个只对世界的娱乐感兴趣的人,尤其注重追求美女。他观察到没有任何道德可以抵抗他的arts和努力,在附近十英里的范围内,几乎没有一个农家女孩没有发现他成功和不忠实。虽然这个描述让我有点痛苦,但它对我的女儿产生了非常不同的效果,她们的面孔似乎因着期待到来的勝利而闪烁着光芒,我的妻子也不例外,对她们的魅力和美德充满信心。当我们这样想的时候,房主来告诉他的丈夫,那位住在家里两天的陌生人需要钱,但是他无法结清账单。「需要钱!」房主回答道,「那是不可能的,因为昨天他已经付给了我们的城吏三英镑,以免为狗偷狗狗而受到鞭打。」然而,房主的妻子仍然坚持自己的说法,他准备离开房间,骂道:「无论如何,我一定会得到满意的答复。」我请求旅店老板介绍给我这位那么慷慨的陌生人,他很快同意,带来了一位看上去是三十岁的gentleman,穿着曾经有褶边的衣服。他的身体很好,脸上有思考的纹路。他的语气有些短小干巴,似乎不理解或不顾 ceremony。旅店老板离开房间后,我无法避免向陌生人表达关心,为他在如此情况下看到一个gentleman,并提供了我的钱包以满足当前的要求。「我非常高兴地接受了它,」他回答说,「因为我最近一个错误,给了我所有的钱,才发现有些人仍然是那样的人。然而,在我借用之前,我需要了解我的恩主的姓名和地址,以便尽快偿还他。」在这一点上,我满足了他的要求,并提到了我的名字、我的不幸和我要去的地方。「这对我来说比我预期的要幸运,」他说,「因为我本来打算今天离开这里,因为洪水最近还没有平息。」我表示了我在他的陪伴中的快乐,我的妻子和女儿也加入了我的请求,他最终被劝说了下来,在那里过夜。陌生人的对话,既有魅力又有教育意义,让我想要继续这种感觉;但现在已经很晚了,是时候休息了,为明天的疲劳做好准备。

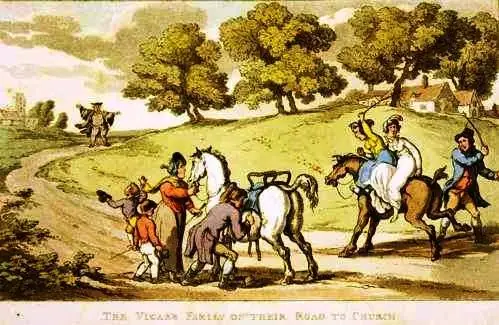

The next morning we all set forward together: my family on horseback, while Mr. Burchell, our new companion, walked along the footpath by the roadside, observing, with a smile, that as we were ill mounted, he would be too generous to attempt leaving us behind. As the floods were not yet subsided, we were obliged to hire a guide, who trotted on before, Mr. Burchell and I bringing up the rear. We lightened the fatigues of the road with philosophical disputes, which he seemed to understand perfectly. But what surprised me most was, that though he was a money-borrower, he defended his opinions with as much obstinacy as if he had been my patron. He now and then also informed me to whom the different seats belonged that lay in our view as we travelled the road. “That,” cried he, pointing to a very magnificent house which stood at some distance, “belongs to Mr. Thornhill, a young gentleman who enjoys a large fortune, though entirely dependent on the will of his uncle, Sir William Thornhill, a gentleman, who content with a little himself, permits his nephew to enjoy the rest, and chiefly resides in town.” “What!” cried I, “is my young landlord then the nephew of a man whose virtues, generosity, and singularities are so universally known? I have heard Sir William Thornhill represented as one of the most generous, yet whimsical, men in the kingdom; a man of consumate benevolence.”—“Something, perhaps, too much so,” replied Mr. Burchell, “at least he carried benevolence to an excess when young; for his passions were then strong, and as they all were upon the side of virtue, they led it up to a romantic extreme. He early began to aim at the qualifications of the soldier and scholar; was soon distinguished in the army and had some reputation among men of learning. Adulation ever follows the ambitious; for such alone receive most pleasure from flattery. He was surrounded with crowds, who showed him only one side of their character; so that he began to lose a regard for private interest in universal sympathy. He loved all mankind; for fortune prevented him from knowing that there were rascals. Physicians tell us of a disorder in which the whole body is so exquisitely sensible, that the slightest touch gives pain: what some have thus suffered in their persons, this gentleman felt in his mind. The slightest distress, whether real or fictitious, touched him to the quick, and his soul laboured under a sickly sensibility of the miseries of others. Thus disposed to relieve, it will be easily conjectured, he found numbers disposed to solicit: his profusions began to impair his fortune, but not his good-nature; that, indeed, was seen to increase as the other seemed to decay: he grew improvident as he grew poor; and though he talked like a man of sense, his actions were those of a fool. Still, however, being surrounded with importunity, and no longer able to satisfy every request that was made him, instead of money he gave promises. They were all he had to bestow, and he had not resolution enough to give any man pain by a denial. By this he drew round him crowds of dependants, whom he was sure to disappoint; yet wished to relieve. These hung upon him for a time, and left him with merited reproaches and contempt. But in proportion as he became contemptable to others, he became despicable to himself. His mind had leaned upon their adulation, and that support taken away, he could find no pleasure in the applause of his heart, which he had never learned to reverence. The world now began to wear a different aspect; the flattery of his friends began to dwindle into simple approbation. Approbation soon took the more friendly form of advice, and advice when rejected produced their reproaches. He now, therefore found that such friends as benefits had gathered round him, were little estimable: he now found that a man’s own heart must be ever given to gain that of another. I now found, that—that—I forget what I was going to observe: in short, sir, he resolved to respect himself, and laid down a plan of restoring his falling fortune. For this purpose, in his own whimsical manner he travelled through Europe on foot, and now, though he has scarce attained the age of thirty, his circumstances are more affluent than ever. At present, his bounties are more rational and moderate than before; but still he preserves the character of an humourist, and finds most pleasure in eccentric virtues.”

第二天早上我们一起离开:我的家人骑马,而我们的新伴侣Mr. Burchell在路边的小路上走着,微笑着说,因为我们骑马不是很熟练,他不会太宽慰地离开我们。由于洪水还没有平息,我们不得不雇佣一个向导,他在前面奔跑,Mr. Burchell和我在后面。我们通过谈论哲学问题来减轻道路的疲劳,他似乎非常了解。但是,让我感到惊讶的是,即使是一个借钱的人,他也用同样的固执地捍卫他的观点,就好像他是我的恩人一样。他时不时地向我指明我们旅行时看到的不同的座位的主人。「那个,」他指着一座非常宏伟的房子说,「是Mr. Thornhill的房子,一个年轻的绅士,享有大的财富,尽管他的财富完全取决于他的叔叔Sir William Thornhill的意愿,一个在城里生活的绅士,他非常欣赏他的叔叔,允许他享受所有剩余的财富,他自己则主要驻扎在城市。」「什么!」我说,「那么我的年轻房东就是那个人,他的美德、仁慈和怪诞行为如此普遍知名的人的侄子?我听说过Sir William Thornhill被认为是一个非常仁慈、慷慨的人。」「或许有点过分了,」Mr. Burchell回答说,「至少他在年轻时对诚挚的善良过于盲目,因为他的情感很强烈,而且都是为了善良;他很快就成为了军人和学者,在军队中表现出色,在知识分子中也有一定的名声。追求成功总是伴随着讨好;因为只有那些人能够让他们感到高兴。他被围绕着人群,而这些人只向他展示了他们的一面;所以他开始放弃了对私人利益的关注,转而关注普世同情。他热爱所有人;因为财富让他免于认识渣滓。医生告诉我们有一种疾病,使整个身体如此敏感,即使是轻微的触摸也会痛苦:有些人在身体上经历过这种痛苦,这位绅士则在心理上经历过这种痛苦。他对任何实际或虚拟的不幸如此敏感,以至于他的灵魂会受到影响,这使他感到生活在一个虚弱的感性之中。因此,他被人们想要帮助的人所吸引,他的财富开始减少,但他的善良却不断增加;他变得不负责任,变得贫穷,但他的行为却像一个明智的人一样,而他的行动却像一个白痴一样。然而,由于他被人们的讨好包围,而且不再能满足每个要求,他开始给出承诺,而不是钱。这是他唯一有价值的东西,他也没有勇气拒绝任何人。这样,他就吸引了一群无法实现的人,他们必须离开他而感到愤怒和蔑视。但随着他变得令人蔑视,他对自己也变得可耻。他的心灵曾经依靠他们的讨好,这个支持被拿走了,他找不到使自己快乐的方法,除了心灵的赞美,他从来没有学会尊敬自己。现在,世界开始有了不同的面貌;他的朋友们的讨好变成了单纯的认可。认可很快变成了更友好的形式——建议,当建议被拒绝时,产生了他们的责难。他现在发现那些聚集在他周围的朋友实际上不值得估计,现在他发现一个人必须永远将自己的心灵交给他才能获得他人的心灵。现在,我发现——发现——我忘记了我想要观察的内容;总之, sir,他决定尊重自己,并设定了恢复他衰退的财富的计划。为此,他用他的怪诞方式通过欧洲旅行,现在即使他还没有到三岁,他的经济状况也比以前更加富足。现在,他的恩惠比以前更加理性和谨慎,但他仍然保留着humourist的特质,并且仍然感到在做出古怪的善行时最感到快乐。」

My attention was so much taken up by Mr. Burchell’s account, that I scarce looked forward as we went along, till we were alarmed by the cries of my family, when turning, I perceived my youngest daughter in the midst of a rapid stream, thrown from her horse, and struggling with the torrent. She had sunk twice, nor was it in my power to disengage myself in time to bring her relief. My sensations were even too violent to permit my attempting her rescue: she must have certainly perished had not my companion, perceiving her danger, instantly plunged in to her relief, and with some difficulty, brought her in safety to the opposite shore. By taking the current a little farther up, the rest of the family got safely over; where we had an opportunity of joining our acknowledgments to hers. Her gratitude may be more readily imagined than described: she thanked her deliverer more with looks than words, and continued to lean upon his arm, as if still willing to receive assistance. My wife also hoped one day to have the pleasure of returning his kindness at her own house. Thus, after we were refreshed at the next inn, and had dined together, as Mr. Burchell was going to a different part of the country, he took leave; and we pursued our journey. My wife observing as we went, that she liked him extremely, and protesting, that if he had birth and fortune to entitle him to match into such a family as our’s, she knew no man she would sooner fix upon. I could not but smile to hear her talk in this lofty strain: but I was never much displeased with those harmless delusions that tend to make us more happy.

我对Mr. Burchell的描述如此吸引我的注意力,以至于我在旅行时几乎没有注意周围,直到我的家人发出惊叫,我才转过身来,看到我的最年轻的女儿被抛在了急流中,正与激流斗争。她已经沉下两次,而我却没有及时将自己解开,以救援她。我的情绪甚至也太激烈,以至于我没有尝试救援她:如果不是我的伴侣迅速跳入救援,她可能会死亡。他立即跳入救援,并有点困难地将她安全带到对面岸。通过沿着更远的流程,其余的家人得到了安全,在那里我们有机会表达我们的感激之情;她的感激之情可能更容易想象,她用眼神,而不是用话语感激了她的救援英雄,并且继续依靠他的胳膊,表示她仍然愿意接受帮助。我的妻子也希望有一天能在自己的家中回报他的恩惠。因此,在我们在下一个旅店里休息并共进晚餐后,由于Mr. Burchell要去另一个方向,他离开了我们,我们继续旅行。我的妻子在旅行中观察到,她非常喜欢他,并宣誓,如果他有资格和我们的家庭结婚,她不知道有什么人比他更适合结婚。我不禁笑着听了她这么傲慢地说话:但是,我从来没有不喜欢那些无害的错觉,因为它们有助于使我们更快乐。